Using a paper-cut shadow-box effect to conjure 3D cars from 2D objects

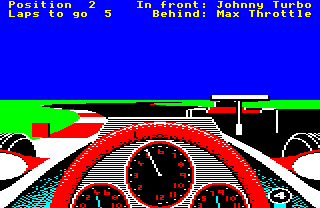

If there's one aspect of Revs that clearly marks it out as an ancestor of modern sim-racing games - arguably the ancestor - then it's the visceral feeling you get of driving around an almost real-world, three-dimensional Silverstone. The game somehow achieves genuine immersion, the feeling of actually being there, and all on an 8-bit, 320x160-pixel, four-colour, 32K machine from the early 1980s.

There's a wonderful video on YouTube from GPLaps showing how Revs performs when hooked up to a modern driving wheel, and it's fascinating to see just how convincing the simulation can be when paired with immersive hardware. Despite the seven-year gap, the 1984 version of Revs really does come across as an early version of Geoff Crammond's era-defining Formula One Grand Prix from 1991.

So what's the secret of this immersion? Well, the low-seated perspective from behind the steering wheel is a key part of it, and so is the sophisticated physics engine that powers the simulation. But just as important is the feeling of being hemmed in by the other cars as you hurtle round the corners, of speeding into the straights and squealing through the chicane. The other cars in the race really feel three-dimensional, as if you really could swerve sideways and force them off the track.

To show you what I mean, here's a car overtaking us at the start of the practice lap. I've slowed this down a bit, but even with the low frame rates and chunky graphics, there's something convincingly solid about the car, particularly when it's close by:

So, presumably there's a 3D graphics engine behind all this magic? Actually, there isn't. The locations and interactions of all the objects in Revs are simulated within a 3D world, but the objects themselves are two-dimensional, like pieces of paper in a paper-cut shadow box - even the car that's hurtling along in the above image is made up of paper-thin 2D elements.

Let's see how Geoff Crammond managed to conjure up a 3D world from a bunch of 2D objects.

The various car objects

-----------------------

All the objects that we see in the track view in Revs, from the cars to the road signs, are stored as 2D vector-based objects that can be scaled to any size. For details of the object system and the objects themselves, see the deep dive on object definitions, and for more information about how these objects can be scaled, see the deep dive on scaling objects with scaffolds.

For the purposes of this article, we're only interested in the first six objects. Between them, these six objects generate three types of on-screen car. Two of these types work in a simple enough way, with one object type being used for cars that are close, and the other for cars that are far away:

| Object type 4 |  | Standard car |

| Object type 5 |  | Distant car |

Things get interesting with the other four objects, which work together to create a 3D car that's made up of four 2D objects:

| Object type 0 |  | Front tyres |

| Object type 1 |  | Body and helmet |

| Object type 2 |  | Rear tyres |

| Object type 3 |  | Rear wing |

If you take a look at the overtaking car at the start of this article, you may be able to spot these four 2D objects coming together to create the 3D car. To make it a bit easier to spot, here's each individual frame from the animation. Try working your way from left to right through the car in the first image below, identifying each of the above objects in turn as you step forward through the car from the rear wing to the front tyres.

| 1 |  | Four-object car |

| 2 |  | Four-object car |

| 3 |  | Four-object car |

| 4 |  | Four-object car |

| 5 |  | Standard car |

| 6 |  | Standard car |

| 7 |  | Distant car |

| 8 |  | Distant car |

The first four frames show the four-object car at various sizes, while the last four show the standard and distant car objects. The first four look convincingly three-dimensional, even though Revs only supports flat, two-dimensional objects, and by the time the game switches to using single 2D objects, the car is far enough away for it not to spoil the illusion. It's a really effective system.

Let's take a deeper look at exactly how the four-object car weaves its dimensional magic.

The four-object car

-------------------

The four-object car is only used for the closest car in front of us, and then only if it's close enough, and only if we are facing forwards. The four-object car always shows the rear view of the car, so if we spin around on the track and end up facing backwards, then all the cars will be drawn using only the standard or distant car objects.

Once you know that the car is made up of four objects, it isn't hard to see how it works. The four-object car uses the same trick as paper-cut shadow boxes to create depth from a series of flat, two-dimensional images, by placing the objects in front of each other, at the correct positions to give an impression of solidity. This approach works on both sides of the screen - there's a good example on the back of the Revs box, with the four-object car to the right this time:

The logic that draws the four-object car can be found in the BuildCarObjects routine. Before drawing any object on-screen, we need to work out the object's screen coordinates and its scale factor, all of which depend on the position and orientation of the object relative to our car and the track. This projection method is explained in the deep dive on pitch and yaw angles, but for the purposes of this article, all we need to know is that the first two parts of the BuildCarObjects routine do the necessary vector calculations for each of the cars in the race, putting the resulting angles into the 20 slots available for the car's 3D coordinates (slots 0 to 19).

On top of these 20 slots are three extra slots, numbered 20, 21 and 22. If we are drawing the closest car, and it's reasonably close and we are facing forwards, then part 3 of BuildCarObjects also populates these extra slots, but this time for the three other objects in the four-object car.

The logic is fairly simple, even if it's complicated by having to be in 8-bit assembler. By the time we reach part 3 of BuildCarObjects, we've already calculated the car's coordinates in 3D space and stored them in the car's standard slot (0 to 19), so we can use this object for the rear wing. To convert this single object into a 3D, four-part car, we simply create three new objects, one for the rear tyres just in front of the rear wing object (i.e. with a larger z-coordinate, further into the screen), and then another in front of that for the body and helmet, and then another one in front of that for the front tyres.

It's the positioning of these extra objects that gives the car its substance. Take a look at this animation of a car sliding sideways, which shows how the four objects move with respect to each other when the car is in different horizontal positions on the track:

The spacing of the four car objects is not equal, though they are in a straight line (with that straight line going into the screen, along the direction of the track). To get the correct spacing, the BuildCarObjects routine first calculates the track vector for the current track section, which is the vector pointing forwards along the inside edge of the track. We then calculate the coordinates for the three new objects by adding either 1/8, 1/4 or 1/2 of this vector to the rear wing coordinates, to get the coordinates of the rear tyres, body/helmet and front tyres respectively.

This makes the rear wing and the rear tyres pretty close, while the front tyres are much further ahead, giving us the correct proportions for a racing car, with the tail almost above the rear tyres and the front tyres well out in front of the cockpit. Here's what the layout of the four objects would look like from the side of the car:

Rear wing -> Rear tyres -----> Body/helmet -------------> Front tyres

The final stage is to project these three objects onto the screen to give us 2D screen coordinates to use for drawing the object. It's this projection process that gives us the perspective we need. If the car is off to the side, then when the four objects get projected onto the screen, they get spaced out differently along the left-right x-axis according to their z-coordinates, i.e. according to their depth into the screen.

We also make sure to draw the objects in the correct order, from the front of the car to the back, so much like a paper-cut shadow box, the four parts end up with a left-right offset that makes them peek out from behind the objects in front of them, depending on the viewing angle. The sliding car animation above shows off this perspective shift nicely.

And the really clever thing? Even when you know that the four-object car is a simple collection of 2D objects, it's still totally convincing as it moves along the track. Take another look:

There may be only one car at a time employing this clever optical illusion, but add in the realistic physics engine and the low-slung view from the cockpit, and it's more than enough to elevate Revs into the realms of the genuine racing simulator.